Existe em português

Many sources online talk about how coffee came to exist, spread and flourish in Brazil but few speak about the early years, about what happened once the coffee plants arrived in the country. That is, the very beginning of what would become the largest and most successful coffee producing country in the world.

It all begins with a secret mission disguised as diplomacy. On May 27, 1727, Major Francisco de Melo Palheta - the man who was tasked with a side mission to covertly smuggle unroasted coffee beans from French Guyana to the Brazilian Amazon - returns to Belém with 5 seedlings. Officially, he had been sent to Cayenne to mediate a border dispute1, but behind the scenes, his true objective was to break the French monopoly on coffee cultivation. While a popular tale claims he charmed the wife of the French governor into secretly giving him a handful of seeds, documents suggest a more practical outcome: Palheta likely negotiated for the plants himself, later reporting the presence of over a thousand coffee trees and 3,000 cacao on his estate.

While Palheta is widely credited with introducing coffee to Brazil, some have speculated that the plant may have arrived earlier through Portugal’s global trade networks [1]. However, no historical or botanical evidence supports this. As early as 1856, Francisco Freire Allemão rejected the idea, and later historians like Taunay also found no records of coffee in Brazil prior to 1727.

What is documented (or at least widely cited) is that Palheta may have been instructed to use covert tactics while in Cayenne. According to the book Dos cafezais nasce um novo Brasil, by Ricardo Bueno, one version of the story includes instructions to pocket some beans [2]:

If you happen to enter a backyard or garden or field where there is coffee, under the pretext of tasting some fruit, you will see if you can hide a few coffee beans with all possible stealth and caution.

However, Bueno notes that this version (without confirming whether the quoted instructions are part of it) was popularized in 1868 by Camilo Castelo Branco, in Memoirs of Friar João de São José Queirós, Bishop of Grão-Pará (my translation). The narrative appears to draw from local oral tradition, supposedly dating back to 17632.

Returning to the historical record, the governor of the capitancy of Grão-Pará3 sent a letter to João V, the King of Portugal, informing him of the arrival of the seedlings, as well as the "a thousand or so seeds", delivered to Belém’s City Council to be distributed among the residents/farmers of the capital city. Palheta himself also took some samples and planted them in Vigia, a small town outside the capital where he both grew up and retired.

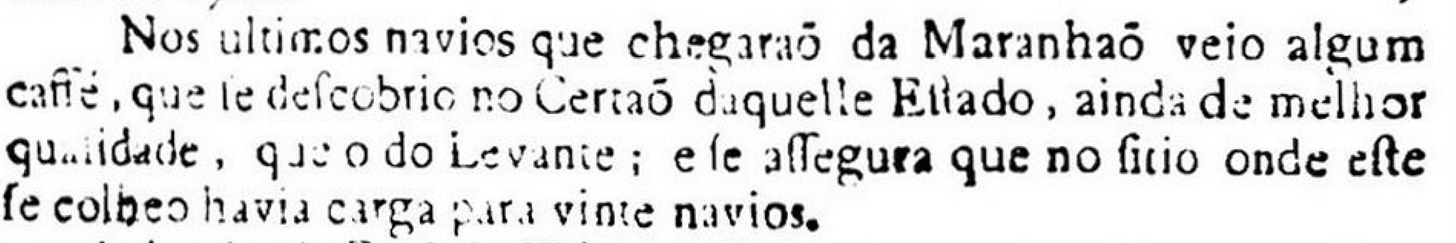

Four years later, in 1731, Portugal’s official government newspaper, Gazeta de Lisboa Ocidental, reported that coffee had come on the latest ships from Maranhão. It claimed the coffee was superior to that of the eastern Mediterranean and noted that 20 ships' worth had been harvested in the region. This fact shows the eventual path that coffee would take as it initally spread throughout Brazil, from Grão Pará, to Maranhão, then Bahia and finally the Southeast in 1760.

But why hasn’t the Amazon taken center stage for centuries as both the birthplace and best place for Brazilian coffee production? The main contributing factor is simply that the region lacked the kind of climate stability that otherwise made the Southeast ideal. Of course, modern agroforestry and genetic improvements have altered this scenario in recent decades.

From five seedlings and a disputed border, Brazil’s coffee empire had quietly begun, not in the Southeast where it would dominate, but in the Amazon, where - despite its abundance of trees and plants - it barely took root.

Sources

1 - Já existia café no Brasil antes de Palheta?

2 - Dos cafezais nasce um novo Brasil, pg 55 (pdf)

3 - Gazeta de Lisboa Ocidental (pdf)

The 1713 Treaty of Utrecht forced France to recognize Portuguese sovereignty over its territory in the Amazon.

The reading of the text suggests the origin is 36-year-old hearsay, that is, from 1763, not a direct archival record

which included what’s now Pará, Amazonas, Amapá, and parts of neighboring states