Em português

Nestled in the highlands of Minas Gerais at 630–1,730 meters, Manhuaçu lies in the coffee-growing region now known as Matas de Minas. Historically part of the broader Zona da Mata (but now classified just north, within the Vale do Rio Doce), this city and its surroundings emerged as a key coffee exporting center for Brazil.

Its journey to coffee prominence was shaped by historical constraints, as Minas Gerais’ lack of a coastline forced reliance on far away ports like Rio de Janeiro and Santos. But why was Minas denied direct sea access, and how did Manhuaçu succeed despite this?

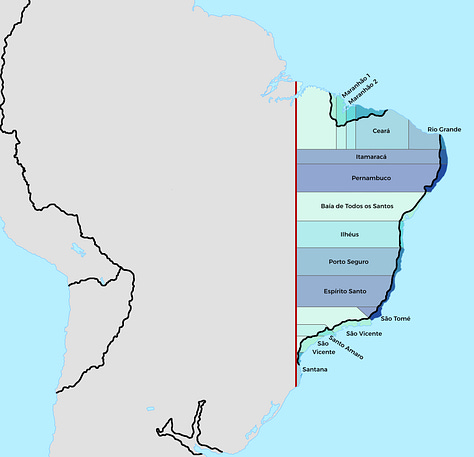

In the 1500s, Brazil’s colonial boundaries were set by the Treaty of Tordesillas, limiting Portugal’s control to just the eastern coast of the continent. Espírito Santo, established as a captaincy in 1535, faced privateer raids from the Dutch, Spanish, and French, prompting close Portuguese oversight. By the early 1700s, gold discoveries in inland areas under Espírito Santo’s loose jurisdiction led the Crown to annex these regions into the Captaincy of São Paulo and Minas de Ouro.

In 1720, this captaincy split into São Paulo and Minas Gerais, with the latter producing 85% of the Portuguese Empire’s gold. To control gold exports and curb smuggling, the Crown routed shipments through Rio de Janeiro’s ports, imposing heavy taxes and blocking Minas Gerais’ access to the sea, just 100 km away via Espírito Santo. After the gold cycle faded in the 1790s, Minas Gerais pivoted to livestock and agriculture, with coffee becoming the state’s main export by 18301. The Zona da Mata led this shift, making use of fertile lands, abundant labor from former mining slaves, and high global coffee prices.

The first to make mention of coffee in Minas was a cartographer in 1788, followed by a historian in 1801, who wrote that it’s a lucrative export to Europe [1]. Yet it had not yet become the driving force it would soon represent in Brazil’s economy.

The first coffee cycle in Brazil, from 1830 to 1850, required a learning curve as the practice of slash-and-burn agriculture, driven by the coffee monoculture, led to rapid soil depletion. As forests were cleared, soils were overused without rest or restoration, and new lands were continuously opened for cultivation. This started in Rio de Janeiro and made its way into the Zona da Mata, leading to the President of the Province of Minas Gerais, Costa Pinto, to make a proclamation in 1838:

The intelligent and wealthy farmer usually keeps part of their land in reserve, preparing it in advance for advantageous cultivation at the right time. Our farmer, however, relies solely on time. Thus, magnificent forests have gradually disappeared, and the soil, covered with useless and even harmful shrubs, is losing its original fertility [2].

Cultivation pushed further into the Zona da Mata - starting from its southern edge near the Vale do Paraíba, then moving through the central region and eventually reaching the north, where the Vale do Rio Doce now lies. Over the decades, large estates gave way to small family farms - in large part due to the Land Law of 18502 - in the period before the second coffee boom (1880–1930). The combination of increasingly rugged terrain - from flatter areas to mountainous zones - and a shifting labor system, from partial emancipation in 1871 to full abolition in 1888, favored the rise of smallholder farming.

In Manhuaçu - which means “big river” in Tupi - was likely an indigenous settlement before explorers entered the region seeking gold and indigenous labor in the 18th century. As mining declined, this area along the Doce River’s tributary network turned to agriculture, like poaia (a medicinal root) and coffee. The Caminho Novo3 opened in the early 1700s and, running directly through the region, had long attracted settlers to the Zona da Mata, boosting the farming opportunities [3].

Ultimately, the Caminho Novo was too long, not directly connecting Rio de Janeiro with Minas Gerais’ main farming regions, Sul de Minas and Campo das Vertentes, making it less efficient by the 19th century. By 1811, the Caminho do Comércio complemented it, better linking these areas to Rio’s coast [4].

The Zona da Mata’s shift from large estates to small family farms, particularly as cultivation moved northward, set the stage for Manhuaçu’s role in the Matas de Minas, where unique geography and climate drove its coffee success. This region’s distinct characteristics and contributions to Minas Gerais’ coffee dominance warrant closer exploration.

Matas de Minas

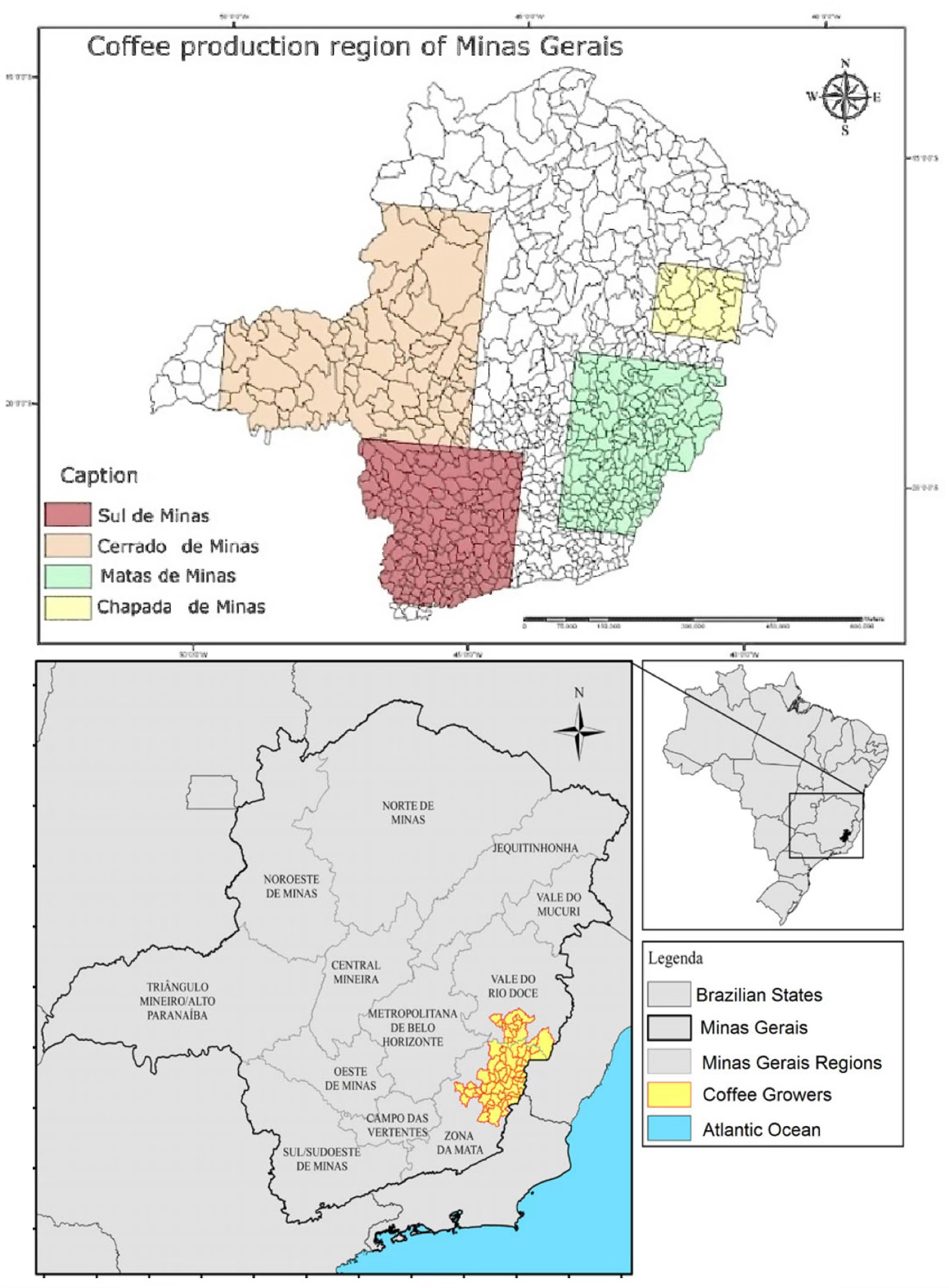

Matas de Minas, spanning 64 municipalities (52 in the Zona da Mata and 12 in the Vale do Rio Doce) features Atlantic Forest landscapes and river basins. Its southern sub-region is drained by the Paraíba do Sul river system and lies within the Zona da Mata, while the northern sub-region is fed by the Doce River’s tributaries and extends into the Vale do Rio Doce4.

The Matas de Minas nomenclature isn’t exactly historical in nature, though5. In 1995, Minas Gerais decided to designate four coffee-growing regions (seen in the upper image below), with the Matas de Minas among them6. Occupying just 3% of Minas Gerais, Matas de Minas now generates 24% of the state’s coffee. And as a whole, Minas Gerais contributes nearly 50% of Brazil’s current coffee output, and holds the claim as the world’s leading coffee-producing region.

But what makes this part of Brazil particularly primed for such agriculture? In the 1929 book Minas e o Bicentenário do Cafeeiro no Brasil, 1727/1927, civil engineer Aristóteles Alvim explained the suitability of the historic Zona da Mata for coffee cultivation:

The entire region is splendidly protected, both against the cold southern winds that cause "wind frost" and the briny sea winds, a scourge to coastal coffee plantations. Along the coast, at a distance of 100 to 300 kilometers from the ocean, natural barriers of the Aimorés and Mar mountain ranges regulate maritime winds, enabling a uniform and suitable regime of warmth and humidity throughout the coffee-growing zone in the eastern part of the state. "White frosts" are also unknown [6].

These favorable conditions allow the Matas de Minas coffee region to grow four main varieties of high-quality coffee: catuaí, catucaí, bourbon and even catimor. Its total annual production is around 7-9 million 60-kg bags, over an area of 275,000 hectares. This covers 36,000 growers - 80% of which are small farmers - and creates 231,000 jobs, both direct and indirect. But it wasn’t always so.

In the early days, coffee was brought to the ports by donkey, and later, by train. The story of how railways arrived in the region, as well as attempts to finally create a shortcut to transport coffee to Espírito Santo, is explored in Part 2.

Additional Information

For the sake of clarification, the Zona da Mata region is both a historical term (covering the whole of eastern Minas Gerais) and a current term (to denominate a southeastern region of the state). Manhuaçu started as part of the Zona da Mata but then became part of the Vale do Rio Doce in 1960. The majority of the Matas de Minas coffee region sits within the current Zona da Mata, while the rest can be found in the Vale do Rio Doce.

Sources

1 - História do café das matas de Minas

2 - Os primeiros tempos do cafe na Zona da Mata mineira

3 - Caracterização e Meio Ambiente

4 - 'Estrada real' do comércio no Brasil Colônia é revitalizada

5 - Matas de Minas official site

6 - História do café das matas de Minas

High food import costs, as the gold cycle ended, drove settlers to agriculture, a boon for the region's subsistence & economy.

The Land Law enabled the legalization of "peaceful and pacified" possessions, allowing first and second occupants to claim cultivated or partially developed land, including virgin areas, provided they established a residence.

linking Ouro Preto to Rio de Janeiro for quicker gold transport, replacing the longer Caminho Velho to Paraty.

distinct from the Zona da Mata

although a 1934 book from Brazil’s Departamento do Café does mention the term “Mata” de Minas.

originally called “Montanhas de Minas” (1995-2001)