Part 1 can be found here

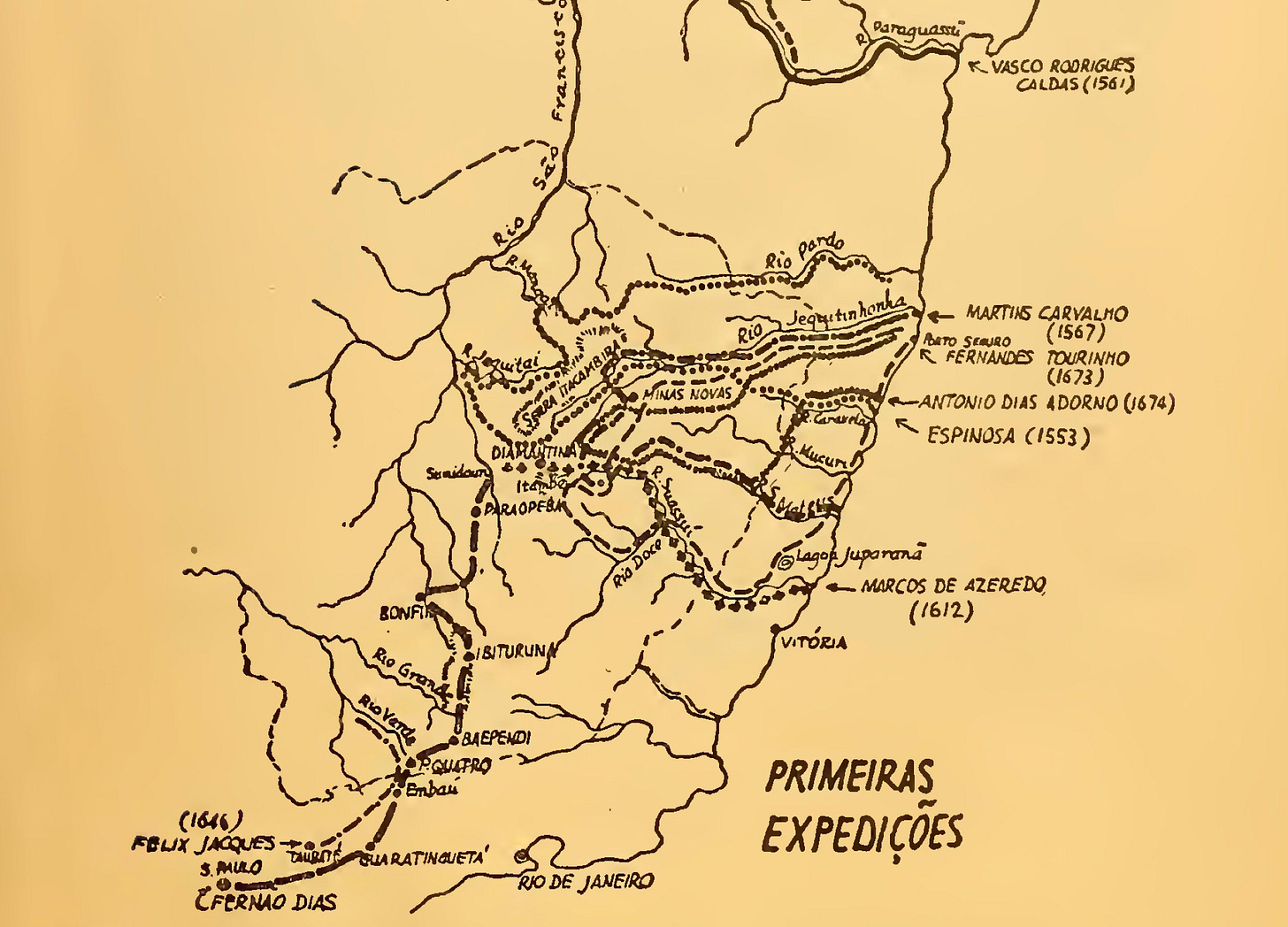

To tell the story of the railways of Minas Gerais and the commerce of coffee in Matas de Minas, it’s necessary to start with the reason for braving the interior of the country. In the early 1500s, the King of Portugal, Dom João III, heard tales of a “Mountain of Esmeralds” situated in the northeast of what is now Minas Gerais. This sparked the dream to connect Minas to the sea, mainly via the Mucuri River at the southern tip of Bahia and the Doce River in northern Espírito Santo.

The Mucuri River, which originates in the highlands of Minas Gerais, near the border with Bahia, and empties into the Atlantic Ocean, was one of the chosen routes for these initial explorers. However, consecutive expeditions throughout the 16th and 17th centuries were unsuccessful due to the thick forests and fierce Botocudos and Puris, Amerindian tribes that occupied much of the region.

Meanwhile, a large expedition was made into the Rio Doce Valley in 1573, led by Sebastião Fernandes Tourinho. Starting with 400 men, mostly Tupiniquim Indians, they navigated through rivers and over land in search of treasures, inspired by the same tales of a "Mountain of Emeralds”. And just like the other expeditions, the same reasons held them back and kept them out.

Considered the first to discover gold in Minas Gerais, Antônio Rodrigues Arzão’s fifty-man expedition in 1693 was anything but easy:

The region took on an impenetrable aspect, "the horizons closed into the unknown," and the backlands appeared vast, mysterious, and unfathomable, with a melancholic and disheartening solitude [2].

It was only with the arrival of the Portuguese Royal family in 1808 that the Rio Doce Valley was divided into six military divisions, with an order to either exterminate or pacify the Botocudos and Puris so that inroads could be made. It was at this point that the Mucuri Valley, called the “last untamed wilderness” of Minas Gerais, was on the verge of colonization. The Crown’s presence now meant that new transport options were opening up to those with the means to see them through.

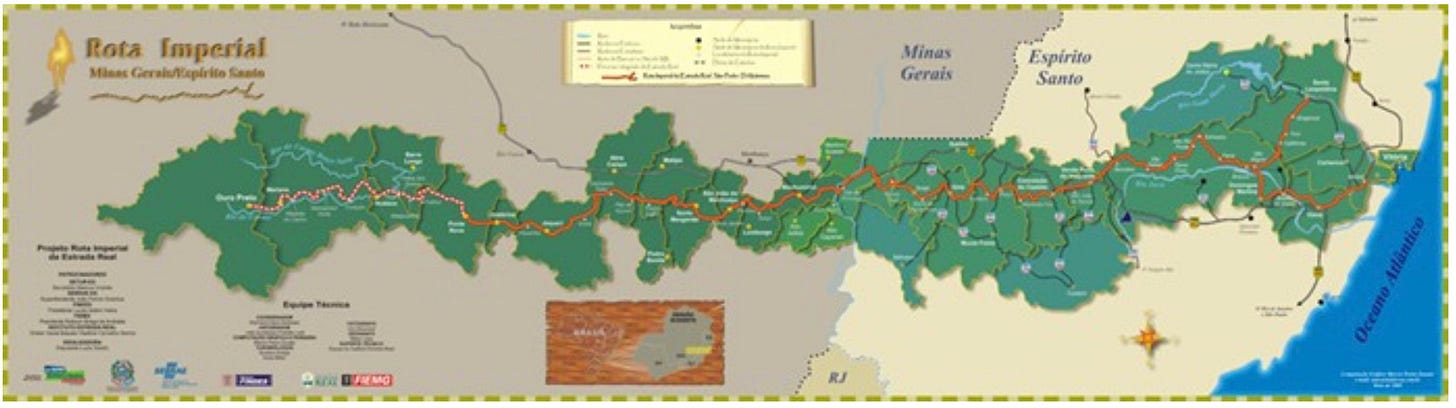

Roads of Connection

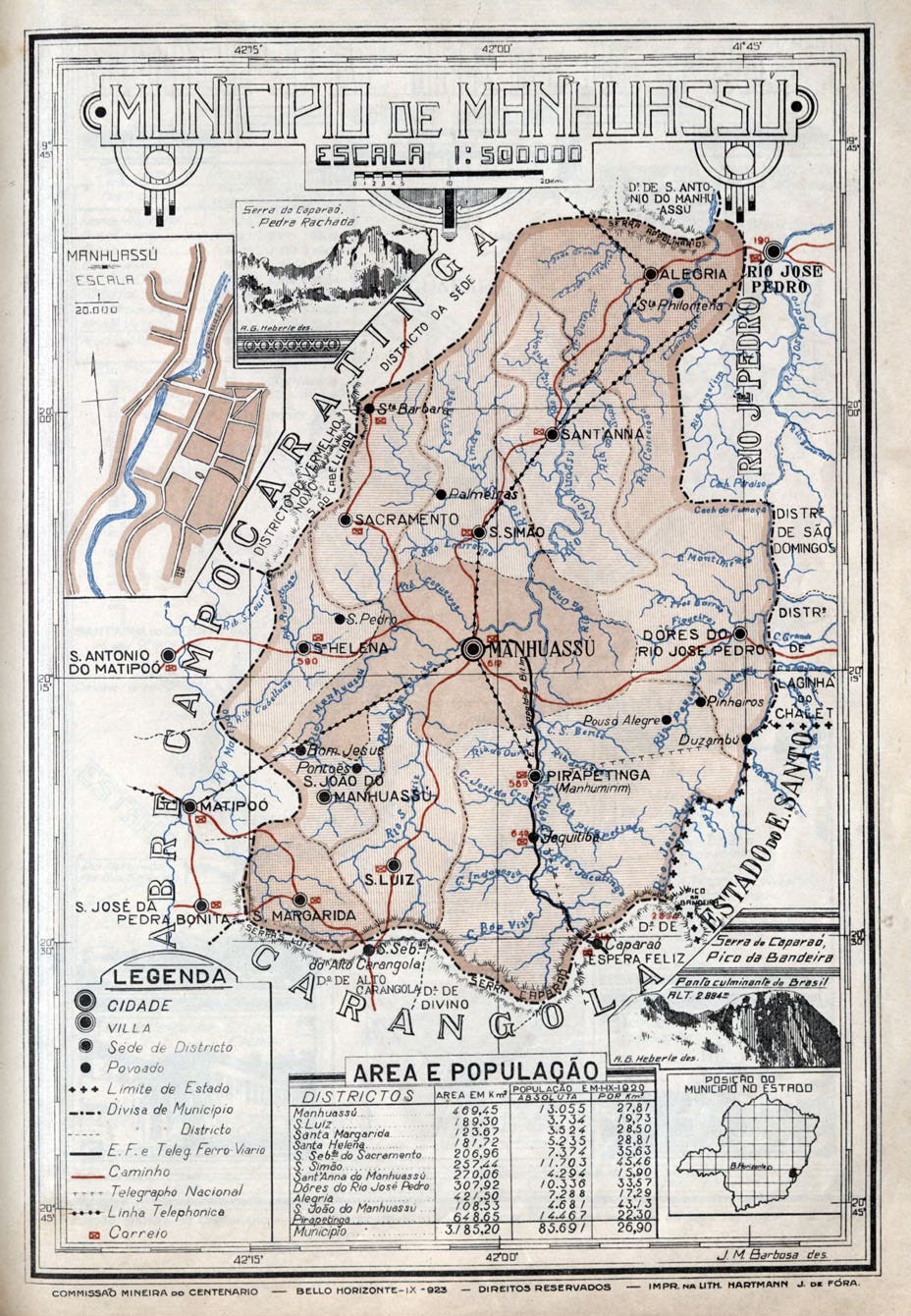

Luckily for the colonists, a royal decree in December 1816 ordered military divisions to open “many and different roads” between Espírito Santo and Minas Gerais. It crossed the Serra do Caparaó, near Pico da Bandeira, and passed over what is now the Manhuaçu river before reaching Ouro Preto [3]. Known originally as Estrada São Pedro d’Alcântara and later as the Rota Imperial1, it was one of several new roads made possible by the decline of gold mining, which had previously led authorities to restrict overland routes to prevent smuggling [4]. Police outposts, chapels and rest stops along the way gave rise to settlements, later populated by Italian, Pomeranian German, Tyrolean, and Austrian immigrants - many arriving during Dom João VI’s efforts to encourage colonization.

Alongside these broader efforts to open new routes, such as the Rota Imperial, the Crown’s 1828 law established regulations for public works, promoting river navigation, canal construction, and the building of roads, bridges, and aqueducts across Brazil2. In the Mucuri Valley, these policies spurred exploration and development. By 1837, a detailed report chronicled a 15-month expedition up the Mucuri River, highlighting its potential. A decade later, in 1847, the Ottoni family secured a concession to establish the Mucuri Commerce, Navigation, and Colonization Company3, launching a maritime service from Rio de Janeiro to the coastal town of Mucuri, with navigation extending into the valley. The same year, another Ottoni brother - Cristiano - requested financial assistance from the Senate to do a technical study of a railway line from Minas Gerais to Espírito Santo.

Through the company, the first wagon-friendly road in Brazil was built in 1853, from current day Nanuque to current day Teófilo Otoni, in northeastern Minas Gerais. The company facilitated colonization4, settling 5,000 German, Italian, Yugoslav, and French immigrant families in the region.

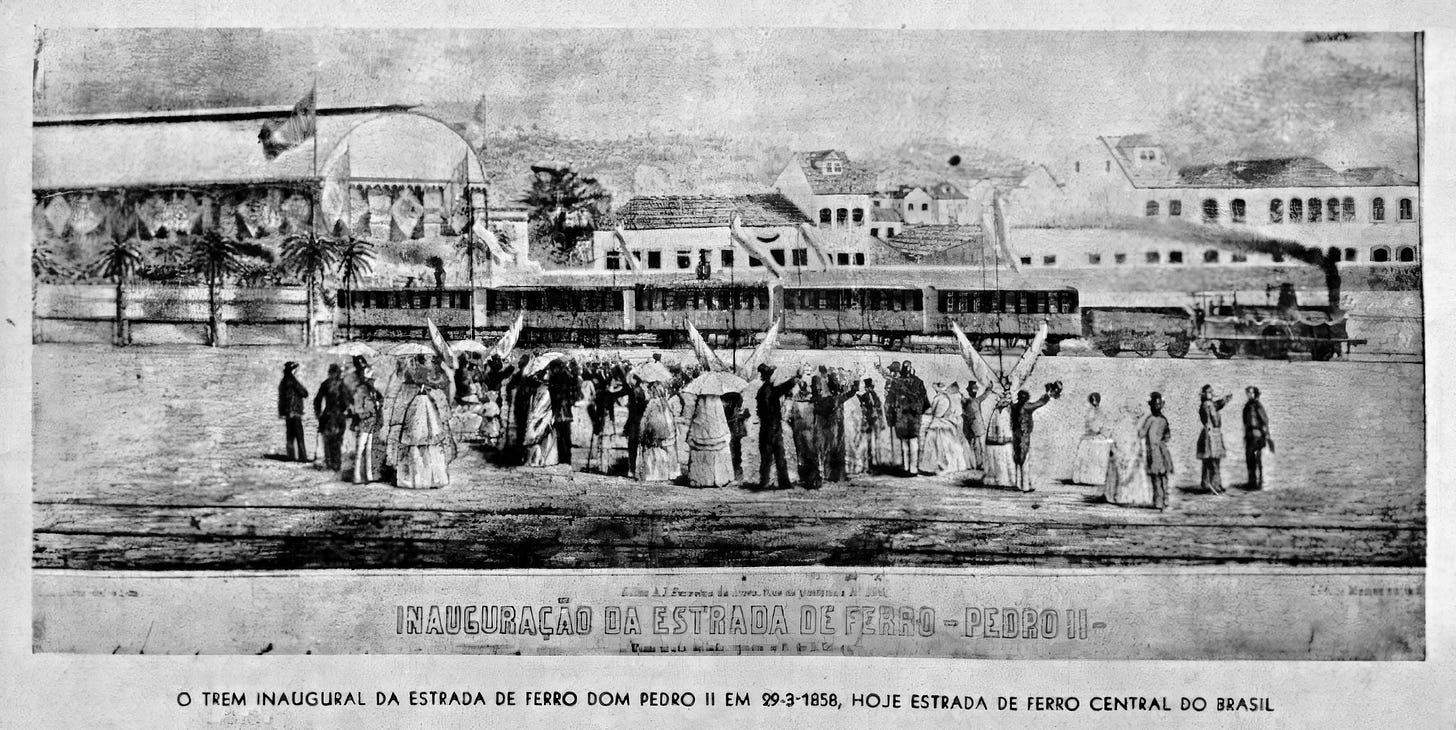

Within two years, Cristiano went a step further than a mere road and became the first and only President of the D. Pedro II Railway Company5. This later earned him the prestigious title of “Father of Brazilian Railways” for his contributions to forging an iron pathway into the heartland.

D. Pedro II Railway

When the D. Pedro II railway launched its inaugural service, Brazil was just beginning to embrace railways, with only two short tracks predating it - one near Petrópolis and another in Recife. Ottoni dared to take it further and forged the way into the Serra do Mar mountains, with the first section inaugurated in 1858. One of the major financieers was the Teixeira Leite family, prominent coffee barons6 of the Paraíba Valley.

Cristiano Ottoni, who would later go on to become both a Congressman and Senator, said the following in regards to his role:

I don't build roads for today's Brazil, but for the Brazil of the future. We cannot split the trains. The trains that run in the lowlands must climb the Serra7 to run on the plateau; otherwise, there will be no economic development possible for the provinces of Minas and São Paulo.

Ultimately, the D. Pedro II - later named Central do Brasil Railway - was quintessential to revolutionizing transport throughout Rio, São Paulo and Minas Gerais, boosting coffee exports and economic integration in the country. However, this wasn’t the only rail network that would streamline mining and agriculture. The subsequent 50 years would see the Leopoldina and Vitória-Minas Railways take on, or try to take on, the heavy lifting.

More rails to the region

The 1870s brought the arrival of the Leopoldina Railway (aka EF Leopoldina) which transformed the Zona da Mata into a leading coffee-producing region. Inaugurated in 1874, it intersected with the Dom Pedro II Railway at the border with Rio de Janeiro, enabling goods to flow from the Zona da Mata to Rio’s ports. Its early presence in the region allowed farmers to shift from mule transport, enabling the Zona da Mata to produce 90% of Minas Gerais’ coffee by the 1880s, though this share fell to 70% by 1920 as other areas adopted the crop.

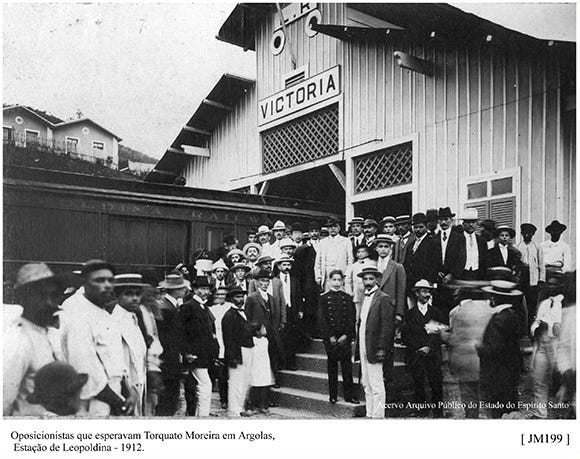

In 1887, the Leopoldina arrived at Carangola (70 km south of Manhuaçu), transforming it into the major center of coffee production for what would become known as Matas de Minas. Carangola became the hub - not only for exporting the region’s coffee but also for receiving goods coming in from Rio. The importance of coffee in the surrounding cities, including Manhuaçu, grew immensely in the subsequent decades, making them their own centers of production [3].

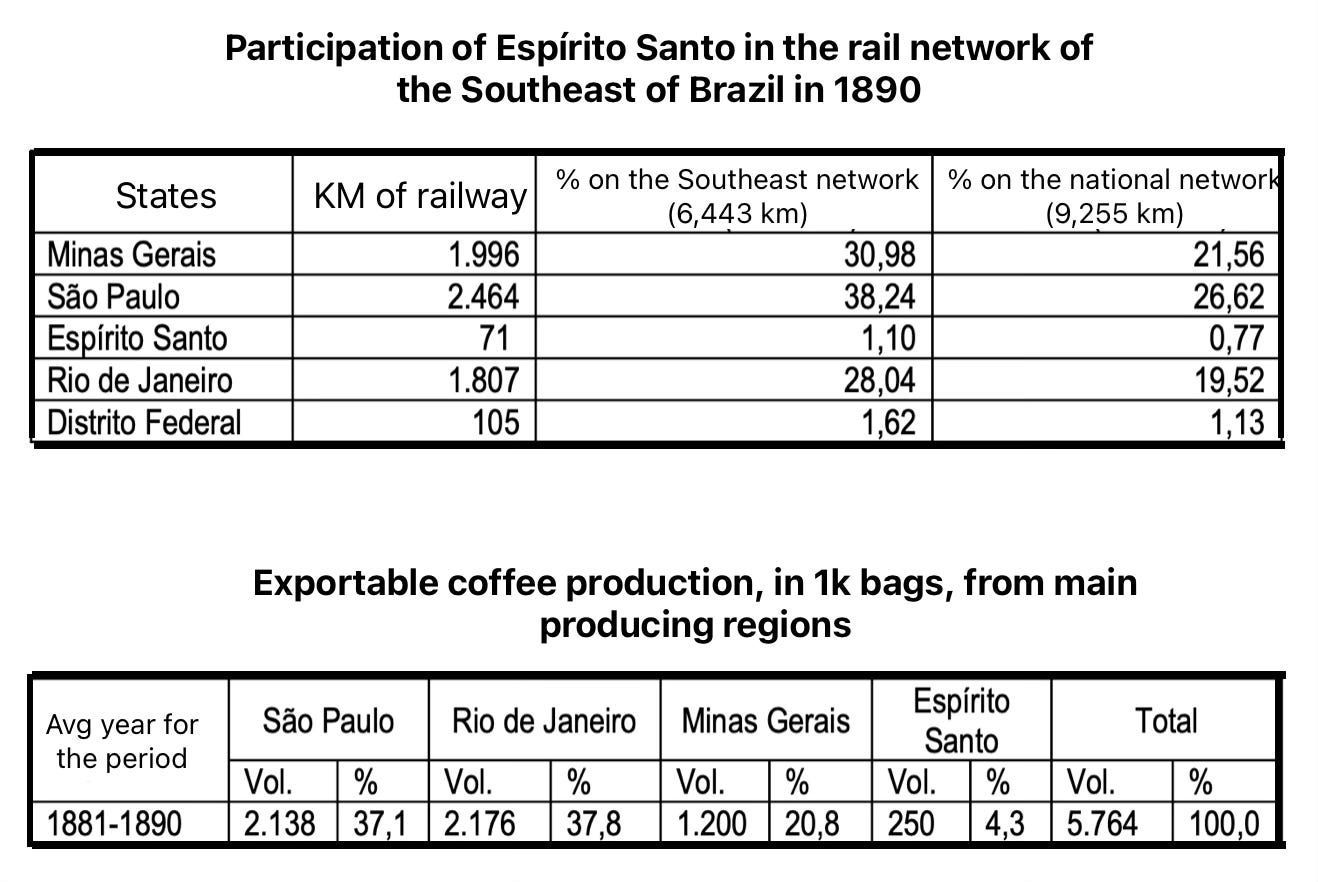

While rail networks in, and through, Minas Gerais were well into their development phase, Vitória was being positioned as a commercial hub to connect Espírito Santo’s interior goods to its port, improving regional economic ties. Aiding in this endeavor, constitutional changes at the end of the 19th century granted states greater autonomy to legislate their own interests, encouraging local infrastructure projects.

As Espírito Santo became the country’s fourth largest coffee producer, it was important to centralize trade at its own port, which meant building out the state’s own rail network. This started in earnest in 1890 with a southern line to ultimately end in Cachoeiro de Itapemirim, which would eventually be bought by the EF Leopoldina [5]. This wasn’t the only new line in the state. The Vitória-Minas Railway (aka EFVM) aimed to provide an easy outlet for the abundant agricultural production of the Doce & Manhuaçu valleys, which had long been hindered and diminished by dependence on slow, laborious, and stunting river navigation.

In an attempt to ease transport distances and costs, as well as fulfill a long-held dream of having more direct access to the sea, the EFVM was authorized in 1890 and finally inaugurated in 1904. An article of the same yar in Kósmos magazine, titled De Victória a Diamantina, captured the era’s excitement:

The export from the Doce River basin, in Espírito Santo alone, reaches one million arrobas of coffee; there are also 40,000 cocoa trees in Porto Mascarenhas and cereals in all the old colonies, from Pau Gigante to Collatina, plus two million arrobas of coffee in the Minas zone. And the future lies in a railway.

For now, the train only reaches 'Alfredo Maia': we returned, and two hours later, the Muquy, under the skilled command of Captain Jeronymo Gonçalves, set sail with us for Rio de Janeiro.

The Penha Convent was no longer visible on the horizon, and I mentally followed the Vitória to Diamantina railway through the opulent hinterlands it would traverse.

I felt its ascendant march to Natividade, freeing the riverside populations of the Doce River from the tyranny of a fluvial artery obstructed by waterfalls in its upper course and closed at the mouth by sandbanks, after the illusion of an extensive navigable stretch; I penetrated Minas. And I saw descending through it, to Vitória, the treasures of Minas, from Manhuaçu to Diamantina: the vast coffee production, valuable timber, rare hides and feathers, abundant and pure crystal, fine gold, precious stones; I saw it fostering industries and cities along its path...

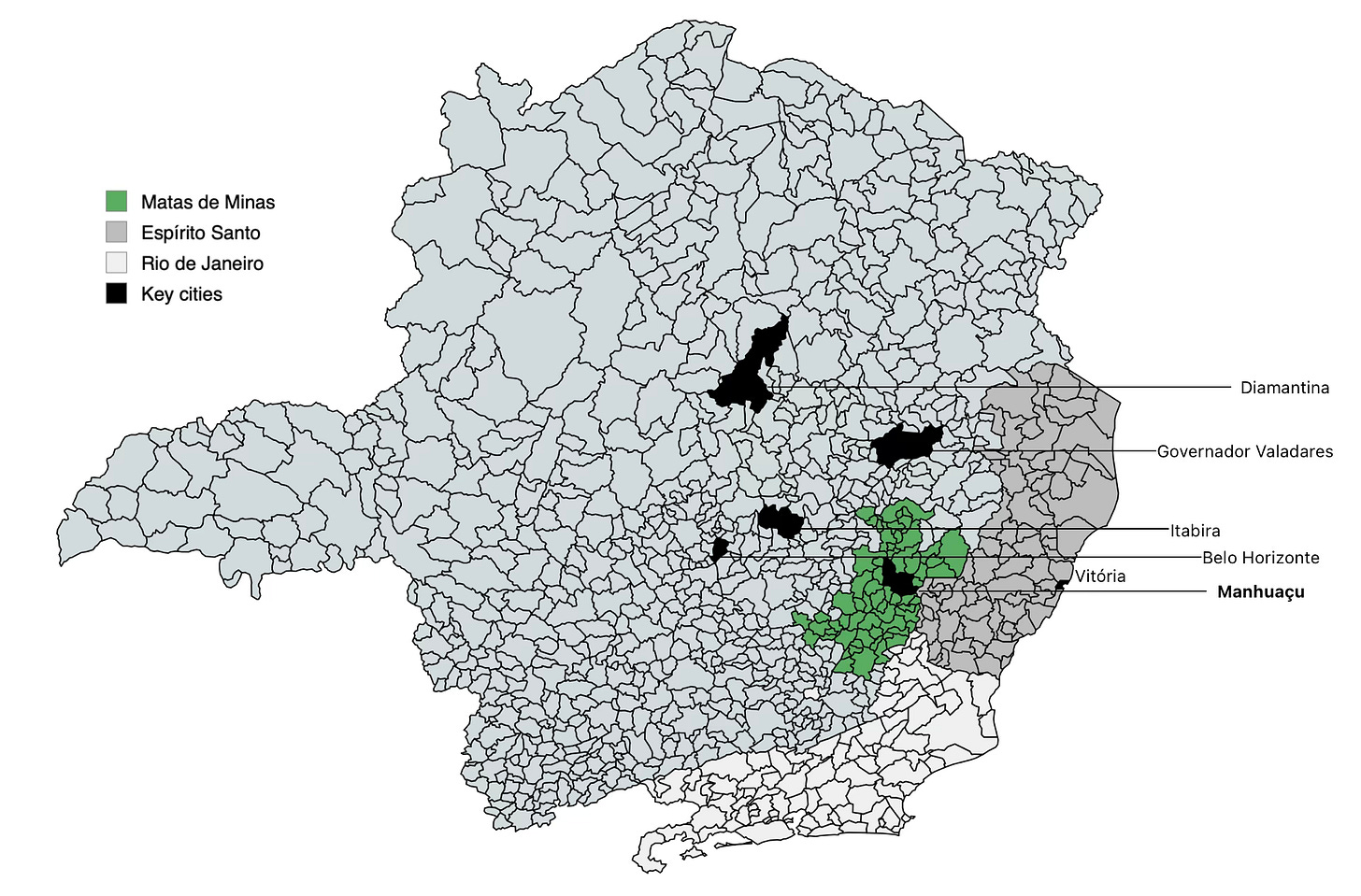

However, by 1908, its focus shifted to iron ore transport after the discovery of reserves in Itabira. The railway followed the flatter Rio Doce Valley to Governador Valadares, avoiding the rugged terrain toward Itabira, which eased construction but bypassed Zona da Mata coffee regions like Manhuaçu (see the image below for reference). Domestic challenges, such as a cholera outbreak and rebellions or revolts in the 1890s, along with global events like the First World War and the 1918 Spanish flu, delayed progress and halted construction from 1914 to 1919.

With the way that the railway enabled steady growth in the coffee trade, it marked the state’s shift from yellow to green gold. Manhuaçu capitalized on this in 1915, after the railway reached the city. By 1920, it was the 5th most important coffee producing city in all of Brazil, responsible for 197.6k 60-kg sacks. Of the 296 stations in the Leopoldina network by 1926, 75% of them exported coffee, with Manhuaçu being the 2nd most important location among those in the Matas de Minas [3]. The Leopoldina ultimately reduced the transport difficulties caused by Minas Gerais’ landlocked position, a colonial policy requiring use of neighboring states’ coasts (as discussed in Part 1).

The coastal access blockade wasn’t just a barrier to commerce; it triggered decades of border conflict throughout the 20th century in the Rio Doce Valley, as detailed in Caminhos do ouro, Minas e mar and other articles [7, 8]:

This contested border region between Espírito Santo and Minas Gerais is a stage for adventure, pioneering, and violence, where large landowners, loggers, farmers, squatters, small agriculturalists, gunmen, vigilantes, police, and local authorities coexist. All play leading roles in a territory where both state governments struggle to assert political and administrative control, with each side accusing the other of invasion when one asserts authority.

An orphaned border region where the law of the strongest prevails, this distinctive culture of violence traces back to the Portuguese Crown’s early 1700s decision to block Minas Gerais’ natural access to the coast via the Rio Doce and prohibit roads connecting to Espírito Santo’s coastline.

By 1970, a coffee leaf rust plague was affecting every major producing state and led to near total destruction of the plantations so the only option was to start again from scratch. Producers across Brazil planted 1.8 billion coffee plants on approximately 1.1 million hectares. They also started incorporating resistant species like Catuai and Mundo Novo, as well as the “use of chemical pesticides, soil correctives and fertilizers, planting on hillsides with contour lines (instead of downhill), proper spacing between plants, harvesting on cloth (to prevent grains from falling to the ground) and other innovations...” [3]. The plan was a huge success. Brazil went from 6-8 sacks per hectare to 20-23 sacks, and the improvements allowed for better distribution which decentralized what areas were able to grow the best coffee. In fact, this redistribution is what allowed Matas de Minas to rise as an important region at both the state and national level.

Eventually, specialty coffee began gaining traction in Brazil with the founding of the Brazilian Specialty Coffee Association (BSCA) in Minas Gerais in 1991, marking a greater importance on quality. While a 1996 law established the legal concept of the "denomination of origin" (DO), Minas Gerais led its practical application at a state-wide level by defining its four coffee-growing regions in 1995 (as mentioned in Part 1). The state was also the pioneer in promoting organic coffee, establishing the Associação de Cafeicultura Orgânica do Brasil (ACOB) in 1998.

The Cerrado Mineiro region, through the Conselho das Associações de Cafeicultores do Cerrado (Caccer) founded in 1992, was the first to make efforts to improve its coffee’s image, implementing the initial certificate of origin that delimited the four producing regions [9]. This effort culminated in the registration of the country’s initial Geographical Indication - the Cerrado Mineiro Region - in 2005, influencing other regions to adopt similar strategies.

As of recently, in 2024, coffee made up 46% of all agribusiness exports in Minas Gerais, which overtook the state’s mining export revenue for the first time ever. In fact, the state exported more coffee than it produced - 28.1 million sacks versus 31 million sent abroad - after demand resulted in producers drawing on stocks stored in cooperatives or private warehouses [10].

This resurgence echoes Matas de Minas’ historical ascent, with Manhuaçu’s 1915 railway connection laying the groundwork for its early prominence. In March 2025, plans emerged to revive the Rio to Minas rail connection [11] in an effort to improve exports, and although its focus is a dry port in Sul de Minas, it hopefully gets authorities & businesses thinking of expanding export-related opportunities across the state. It makes sense to pursue all such avenues, as the region’s specialty coffees - highlighted by a R$ 7,000/sack auction in late 2024 [12] - affirm Matas de Minas’ enduring legacy, blending tradition with modern quality on the global stage.

Sources

1 - Album Chorographico 1927: Manhuaçu

2 - História da Estrada de Ferro Vitória à Minas (pdf)

3 - História do café das matas de Minas

4 - Rota Imperial completa 200 anos de história, no ES

5 - A estrada de ferro Sul do Espírito Santo e a interiorização da capital (pdf)

6 - “Manhumirim”, Revista da Semana (Nov 1946)

7 - Caminhos do Ouro, Minas e mar (inaccessible outside Brazil)

8 - As marcas do Contestado 50 anos após o litígio entre mineiros e capixabas

9 - Diagnóstico sobre o sistema agroindustrial de cafés especiais e qualidade superior do estado de Minas Gerais (pdf)

10 - Minas exportou mais café em 2024 do que produziu, contribuindo para o recorde do agro

11 - Governo Federal dará prioridade para ferrovia que liga Angra até Minas Gerais

12 - Cafés das Matas de Minas brilham em leilão com saca arrematada a R$ 7.000

now a touristic route

in essence, PPPs, or public-private partnerships

one of Brazil’s very first C-corps

facilitated by the 1850 Land Law

aka EF Dom Pedro II (EF means Railway)

previously mining barons

Serra do Mar mountain range